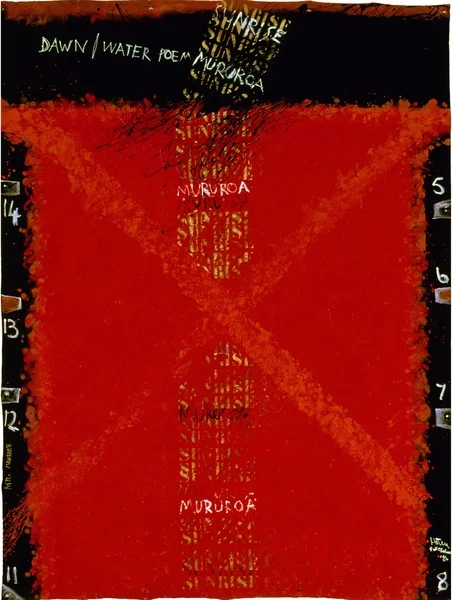

IT TREMBLES TO CARESS THE LIGHT

James Casebere: La Alberca, 2005/2006

Photo: courtesy Goetz Collection

“Epilogue

Those blessed structures plot and rhyme-

why are they no help to me now

i want to make

something imagined not recalled?

I hear the noise of my own voice:

The painter’s vision is not a lens

it trembles to caress the light.

But sometimes everything i write

With the threadbare art of my eye

seems a snapshot

lurid rapid garish grouped

heightened from life

yet paralyzed by fact.

All’s misalliance.

Yet why not say what happened?

Pray for the grace of accuracy

Vermeer gave to the sun’s illumination

stealing like the tide across a map

to his girl solid with yearning.

We are poor passing facts.

warned by that to give

each figure in the photograph

his living name.”

A painter's vision is not a lens. Except, in the case of James Casebere, when it is.

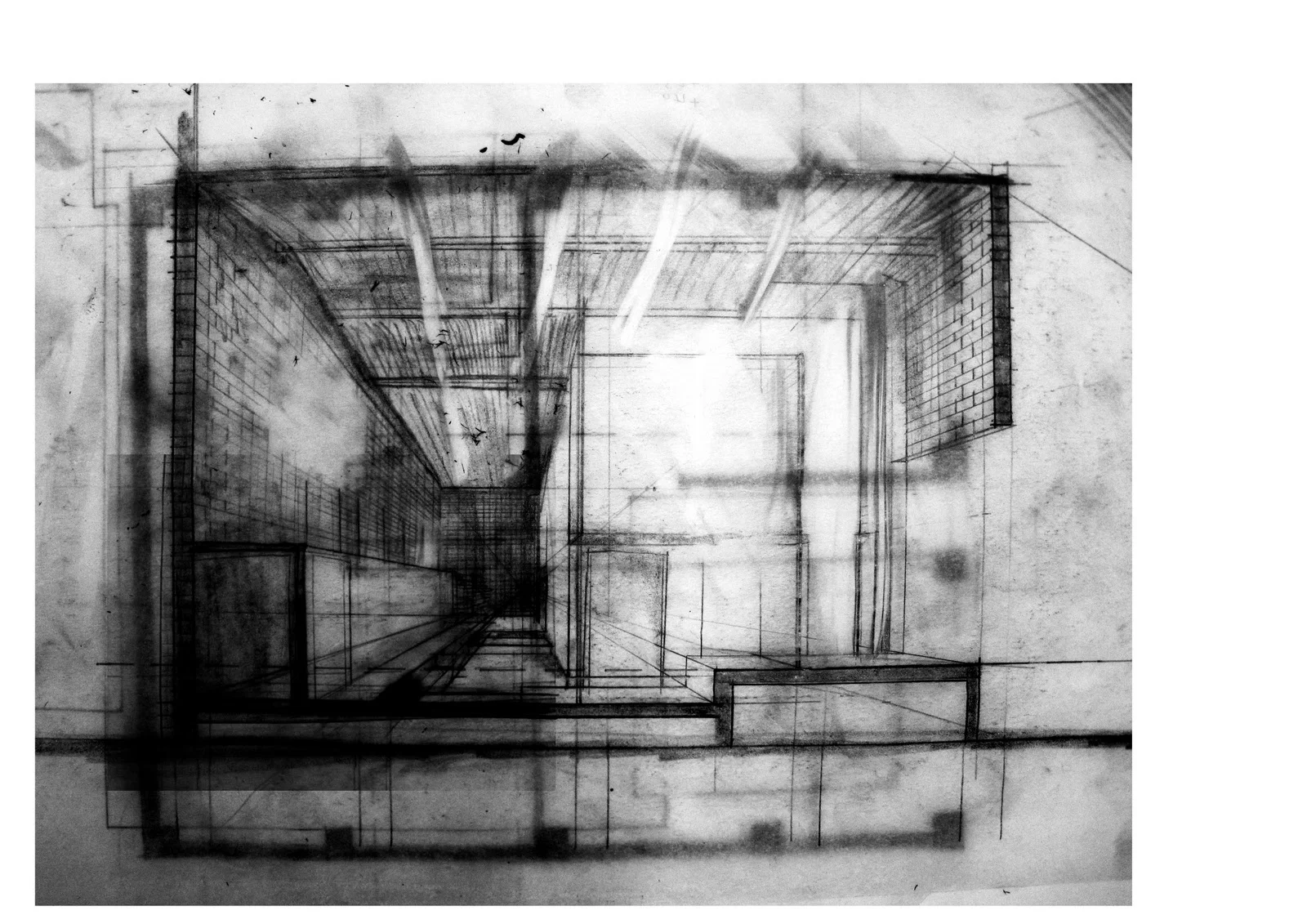

Following this, it is relatively easy to say that his images are heightened from life, yet paralysed by fact. His images trounce the real, they are contaminated by fiction. Is it photo, is it painting? The illumination characteristic of his work is at its most ambiguous in La Alberca. Here, the combination of the abstract, shallow reflective pool of water melts all solidity, returning the physical to its liquid state. The source of illumination is not clear - we are contained in the gestural space.

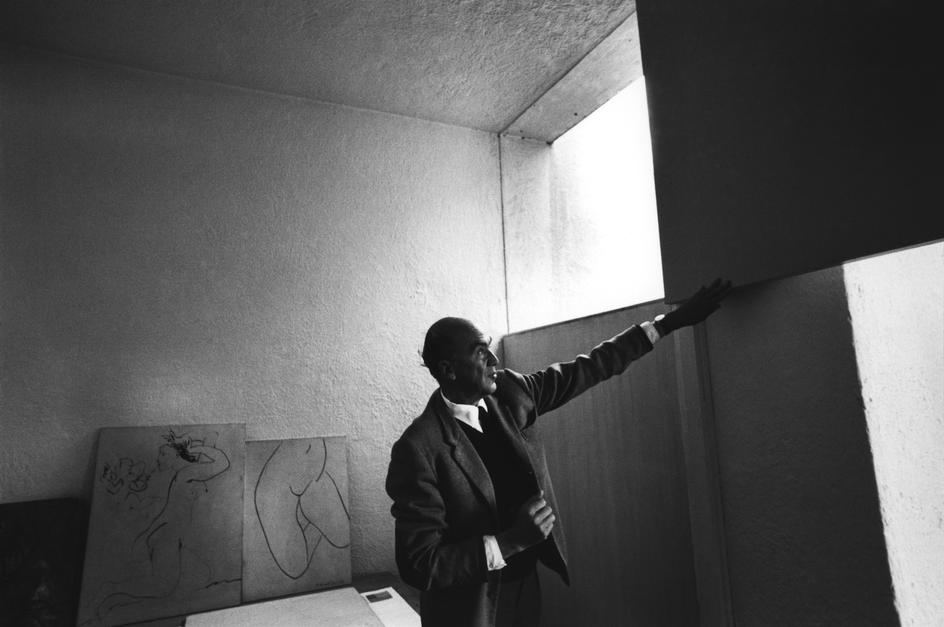

To talk about La Alberca with Lowell's Epilogue hovering at the front of my mind directs me to a correlation between Vermeer and Casebere. I note that Vermeer's work nearly always contains a window - an explicit announcement of the how and why light enters. Casebere, conversely, is not concerned with the entry of light, but with the what the illumination allows.

But even this distinction is not as clear as it might appear. Both artists obsess over how light returns the eye to reality - both artists tremble to caress the light. For Vermeer, painting the everyday Milkmaid was a subject of both stark reality and highly institutionalised myth. His illumination works to bring together these two isolated views. For Casebere the same is true - light folds together the reality of space and the myth that physical material alone is form giving.

Vermeer, The Milkmaid

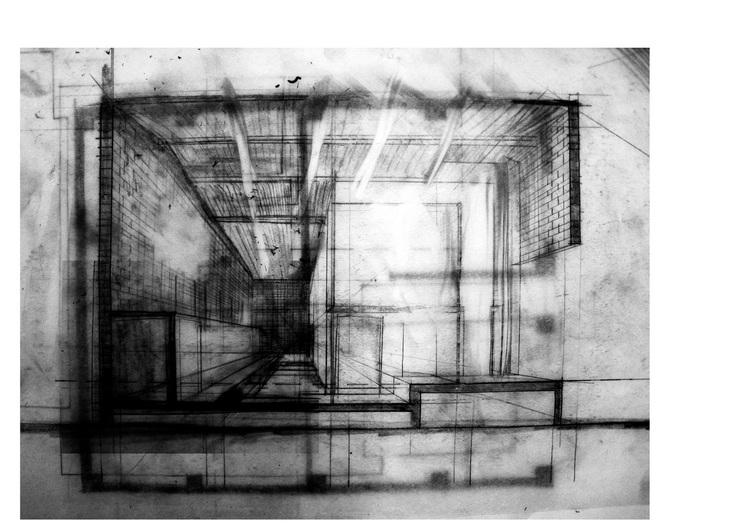

Casebere, The Flooded Hallway

Casebere.