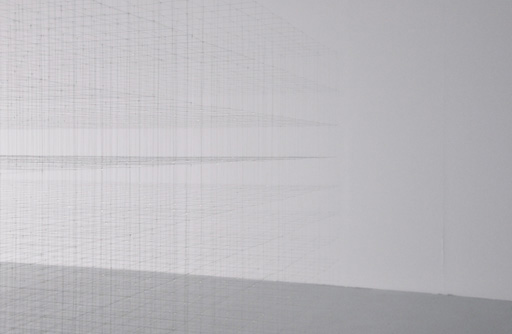

NA HOUSE

Oh, to live in such a cloud!

THE CRAFTSMAN

The Guardian Books have a great review here; and bi-blog 'rhythm' section features a discussion of craft and skill via rhythm here. John Howell has written a more in-depth academic appraisal here.

PROJECTED PASTS

New Zealander Mike Hewson is an engineer by training, yet is about to give up his job in Australia to move back to New Zealand and pursue his artistic practices, which until now have been a sideline, full time. And it's a good thing too!

His most recent installation works are hauntingly beautiful: crisp, blue and sepia-toned photos of what was are projected onto the urban gap spaces left in the wake of the Christchurch earthquakes.

At re:Start Cashel Mall, the aptly titled "View from Studio" projects what was once the outward view onto what was once the window, asking by-passers to consider a smaller moment of what was touched by the iconic Cathedral.

.jpg)

Nearby, the former Christchurch Normal school, which is soon to be demolished, is re-inhabited by vivid photographs of the artists who once lived and worked there. Architecturally, I am also quite enamoured with how the plywood, onto which Hewson projects, sits within the existing structures. This kind of honest approach to time and destruction, rather than merely demolishing, would make for a beautiful city. The simple material infill marks, rather than attempts to erase the pain and destruction.

You can follow Mike's work as he progresses into full-time artist here.

OUTWITH

|

| Kevin Townsend |

1

We might want to think about this question of holding. Maybe we want to notice that it goes

to the limit. This is true: that what we hold, and how we hold it, is a limit on us. It is an

ethical question, this question of style.

2

It is complicated in the case of apples. If one does like apples, how does one hold an apple in

such a way that the apple, not the holding, is what gets shown? For Oppen it is a question for

poetry. ‘The question is,’ as he puts it, ‘when will there not be a hundred/ Poets who mistake

that gesture/ For a style.’

Oppen is shrewd, and also wrong. If style is an exercise of radical will – the assertion of an

individuality – then we might agree that a gesture is preferable to a style. We might agree

that gesture and style were different. We might nod towards the apple. That’s that.

Go further though. Consider disparate elements. Consider disparate elements held together.

Consider that the holding is not necessary, that it is an intellectual act. The elements held

together are an instance of style.

Style is a holding of disparate elements.

Not apples, elements. The question is: which?

3

It is complicated in the case of people. In Giorgio Agamben’s State of Exception, Giorgio

Agamben writes about holding. He writes about States and what they hold; about those they

don’t hold: the state of exception.

Everybody is held, and everybody not held is also held. The state of exception is a special

kind of holding; a place (though not always a place) where those not held by the State are

held.

Style is a relation with elements not ourselves.

More after the break, or read it (in a nicer pdf version) via Almost Island.

4

In State of Exception by Giorgio Agamben, Giorgio Agamben writes at length about the

grammar of the ban. The ban is the answer to the question: how does that which is not held

get held? How does the state hold people it doesn’t opt to hold?

Giorgio Agamben makes the point that the ban has an infinitely supple grammar, that to

issue a ban is to address everybody such that some people are separated out. To effect a ban

is to address everybody, even those held outside. The ban is the linguistic manoeuvre by

which those not held are held.

‘… a holding … (also known as a ‘style’)’

It is an ethical question, this question of holding.

5

On the cliffs above Dover, looking out towards France, nearby where this writing comes

from— down the road just, at a global level in the writing’s dooryard— there is a building that

was once a Napoleonic Fort.

It was a Napoleonic Fort because it was built in the time of the Napoleonic Wars, in order to

stave off invasion by Napoleonic France. The invasion never came and the building wasn’t

finished till the war was. Still, the building served a purpose.

Disparate elements. Sarkozy. When Matthew Arnold wrote ‘Dover Beach’ he didn’t observe

the building.

Still the building served a purpose, and since it was built has had several afterlives. In the

1970s it was a borstal. Since the 1990s it has been an immigration removal centre.

Borstal: so-called from a village outside Rochester, Kent, on the doorstep just, in the

dooryard so to speak.

So to speak, the removal centre isn’t a removal centre. It is a place where people are held.

Indefinitely.

It stands at the limit. A question of holding.

From the cliffs it is possible to witness France.

6

In State of Exception by Giorgio Agamben, Giorgio Agamben observes that the exception is

the rule; that the exception is the rule by which modern jurisdictions sustain themselves;

that the cliffs at Dover is where the reality of modern expression is.

There, on the doorstep, in the dooryard so to speak. It is an ethical question, this question of

holding. It is a language question also, so to speak.

‘ …. a holding together … (also known as a “style”).’

7

Style can’t be the word. ‘The question is/ When will there not be a hundred/ Poets who

mistake that gesture/ For a style.’

If style is an act of radical will, an assertion of individual identity, the word for the ethical

question is not style.

But style is a holding, a decision about what to hold. It goes to the limit, marks the extent of

us.

Style is a relation with things that are not ourselves; in the dooryard, so to speak, a turning

out.

Not a turning out. A turning outwards.

Witness language.

The figure of outward.

8

The question is: what does the figure of outward signify? It is important not to underestimate

the urgency of this issue. Style is a limit, a decision about what we hold. The question is, how

to style a language that is outward?

9

What it comes to is how we turn. Oppen mistrusts style because he considers it a turning

inwards. To hold the apple who likes apples is to hold an apple in such a way that the apple,

in being held, doesn’t become a trope.

To trope is to turn, to turn repeatedly in the language, so that in turning one arrives at a

figure of speech. A style formed by troping is a turning of language towards itself. A gesture,

by contrast, is a turning outwards.

For Oppen style is a figure of speech, a repeated turning within the language. Only by the

gesture, as he sees it, does language get beyond itself.

But what about the figure of outward?

‘For Robert Creeley— Figure of Outward’ (Charles Olson, The Maximus Poems)

10

We might want to think about this figure of outward, about what and how it allows us to

hold. We might want to think about the Dover cliffs, and how the people to be removed are

held outside. Indefinitely. In a state of indefinite detention.

In State of Exception Giorgio Agamben is clear, exception is the rule. Routinely people are

held indefinitely because the nation state is a holding out.

If we take him seriously, Giorgio Agamben, if we think seriously about the building on the

cliffs, looking out from Dover, witnessing France— if we worry about holding, about how

people are held, then we might want to think about the figure of outward.

11

It is question of association, this question of outward.

Consider the associations by which we style ourselves. Consider the tropes, the repeated

turnings, the turnings upon turnings, out of which a culture gets made. Consider the trope as

an association upon which culture turns. Consider the turning of a culture as an inward act.

The figure of outward is a form of association that is a holding together of disparate

elements. It is the opposite of the trope. It is a movement in language away from itself.

A holding together of disparate elements is a form of association in which convention is not

the key. There is this, we might say, and this. In the dooryard there is this. We might extend

ourselves, find a writing in such disparateness.

12

If we think about this question of holding, we might think again about the question of style.

Style is an ethical question, a question of limit. At the limit is that which is not ourselves.

Style is a way of handling that which falls outside. The call is for a style which is where the

outer is.

We can only hazard. Pause. Abstraction.

Breaks. Acknowledgements. Everything but ourselves.

In the dooryard a turning outwards predicated on the new reality.

A holding. Out.

Outwith.

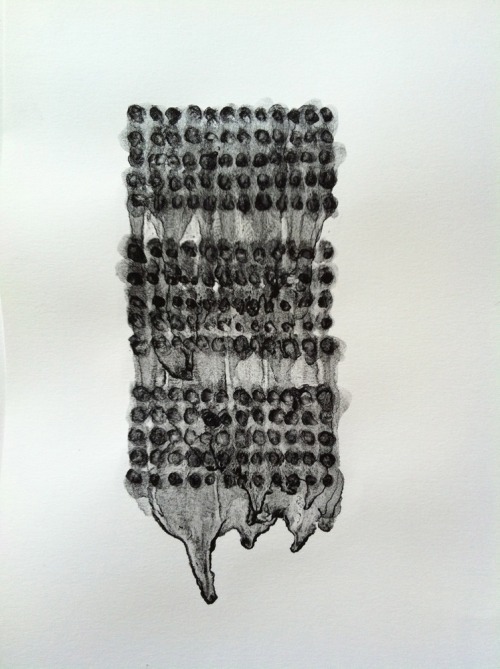

HANDS ON

Perhaps, in a blustery southerly later this year, when you find yourself wandering into the Supreme Court in search of warmth, you will raise your hand and set it, fingertip to fingertip, on the copper against the print of some other person who has been here and admired this place before you.

Thoughts a Year on from the Supreme Court Opening

- 30 June, 2011

It is not easy to avoid hands when you design a building. A little over a year since the opening of the Supreme Court and the adjacent newly-refurbished Old High Court in Wellington and this much is clear. Step inside the Supreme Court and there in front of you, all over the copper-clad shell of the court room, are handprints. Hundreds of them. Smudged, smeared, but definitely handprints. Curiously though, if you step inside the newly-refurbished Old High Court, a building with 120 years of use, you will struggle to find a mere fingerprint.

From the outside, there is little astonishing about the Old High Court building. Where it once would have boasted harbour frontage, its vista today is crowded out by the high rises of the 1980s which make a mockery of its classical arches and hoods in the name of post-modernism. Amidst this sea of new buildings, it is difficult to spot the relatively modest Old High Court. Instead of opening out to the lively, pedestrian Lambton Quay, the entrance is on the less-used Stout Street: less used, because Stout Street happens to be notorious for its wind funnelling functions – a notoriety difficult to earn in the typically blustery capital.

Despite today’s appearances, in 1881, when the High Court was first opened for a service to justice that would last over a century, the classical masonry building would have been a beautiful rarity. Due to flexibility in earthquakes, the majority of building work being undertaken in Wellington at the time was in timber. In fact, the High Court was the first major masonry building commissioned by the New Zealand Government. Architect P.F.M Burrows referenced a highly academic classical style, imbuing the building with dignified proportions, hooded windows and Corinthian pilasters. With its T-shaped plan and hand-sculpted keystones, the High Court brought an exotic taste of the great Italian architect Antonio Palladio to Wellington.

Yet it is the inside, the curved double stairs leading to the public gallery, the detailed carved timber frieze and the broad judge’s bench which give the building its real value. These dark timber rooms were touched by the hands of judges and defendants, nearly non-stop at times, for over a hundred years.

In 1993, a more modern, more spacious High Court meant that permanent use of the Old High Court stopped, and by 1999 the gates were locked for good. For over a decade, the building sat listlessly, completely untouched. Without a daily, or even weekly hand caressing the hundred year old door knocker and tracing the double-curvature of the dark timber banisters, the building fell into degradation.

On the outside, restoration was needed to defeat the effects of time and weather: inside, extensive foundation work was required to make the building earthquake proof – if such a certainty is ever possible. To do so the entire building was raised off its foundations and ‘base isolated’, meaning it is essentially put on a layer which, much like jelly, allows the ground to move separately beneath it. The worn interior panelling was replaced with matching native timbers, and modern technology was woven through the thin walls. Every surface was scraped clean, returned to the untouched building of 1881.

This restoration was completed alongside the development of an adjacent plot of land – what had been an almost equally derelict park – into a building housing the newly formed Supreme Court of New Zealand.

When the buildings were formally opened on the 18th of January 2010, Prince William shook hands with Prime Minister John Key. Prince William’s outreached hand recognised, even congratulated, New Zealand as an independent nation. Prior to 2004, cases that passed through the High Courts and the Courts of Appeal in New Zealand were resolved by a Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, in London. The Supreme Court, initiated as a homeless entity in 2004, recognised New Zealand as an independent nation, no longer needing to rest on the crutch of Great Britain to resolve judicial matters.

Bound up in these questions of independence, nationality, identity and justice, the Supreme Court always had to have high ambitions architecturally. Money was not spared, and the public have been equally open-handed with their criticism. Most of the negative voices have been directed at the 90-tonne bronze screen, patterned and inset with reddish-florets to resemble the pohutukawa and rata trees which grow in the North and South Islands respectively. The public seem unconvinced by this image translation, by the cost and by the sheer massiveness of the screen, which wraps the entire second floor of the two storey building.

Under this screen, the ground floor is open and transparent, working to make justice more accessible. The glass walls are flanked down all sides by large concrete columns. Unlike the columns of the Parthenon in Athens, which taper upwards so that the top is narrower than the base, increasing the effect of perspective and making the columns seem taller and more slender than they actually are, the Supreme Courts boasts columns which taper downwards. The result is that each of the perimeter columns standing outside the building and supporting the second floor looks stout. Rather than appearing to float, as Le Corbuiser’s similarly-proportioned Villa Savoye did, the Supreme Court is heavy, squashing the open ground floor from above.

But the Supreme Court is still a new neighbour, and it will take a good many years before we really see how it gets on with the other buildings in the street. When you enter, there is a small pamphlet (which neatly pops out to eight times its size) explaining the building, from the plan to the copper shell concept. Certainly, hands have been clapped for the intricate geometries achieved in the construction of this copper-shell court room, whose interior is sheathed with timber diamonds, a design supposedly derived from the kauri cone shell. Heads have nodded to the energy efficiency of the building, whose raised moat helps to regulate temperatures, and to the relationship of the new building to the old, most evident in the symmetry of the plan.

But few, neither critics nor admirers, have had much to say about the experience of entering the Supreme Court. Is it a nice place to be? What no one talks about is whether, after shaking hands with one another on that warm day in January, Prince William and John Key walked up to the great copper shell and placed their hands on it, feeling the coolness radiating from it. What no one talks about is the handprints.

Tadao Ando, a well-known Japanese architect who design buildings with large concrete slabs, pours the masses of concrete in one go from ash-laden mixtures. Ash: because the fineness of the grain makes the concrete incredibly smooth. In his buildings, visitors are known to walk around with one hand running across the wall at all times. For real concrete-lovers, the touching hand might be replaced by the more intimate cheek.

So it is not odd that, given the smooth, voluptuous egg-like shell housing the court room, visitors are drawn to placing their palm on its curvature. Despite all the sniggering that accompanied the unveiling of the bronze screen, people feel something for this building. They want to reach out and touch it.

What is odd is that in an institution of law and order, the smudges of the hands of the people are never wiped clean. Perhaps someone has realised that it is these smudges, these hand prints and finger smears, that link stubby concrete columns, a copper shell and bronze screen to the people of today; and that it is the people, the users, who make a building what it is.

Copper, you may know, turns green with age. This is called a 'patina', and it is why the great cathedrals of Europe have brilliant verdant green roofs - they were once copper. In buildings, this process is known as ‘weathering’ because it is commonly caused by exposure to the elements: sun, wind, and rain. Across Europe, ancient and much adored sculptures have had their busts and buttocks rubbed to a shine by the hands of visitors. A fourth, less-discussed element also causes weathering: people.

In the restoration of the Old High Court, the weathering of people, the marks of our predecessors, were removed. Perhaps when someone looks at the Supreme Court in 120 years, they will notice a green tarnish encircling the copper shell, greenest at about 1.5m above floor level. Perhaps, in a blustery southerly later this year, when you find yourself wandering into the Supreme Court in search of warmth, you will raise your hand and set it, fingertip to fingertip, on the copper against the print of some other person who has been here and admired this place before you. The most satisfying part of architecture is not how it looks, or how technically advanced it is. The most satisfying part of architecture is how it connects us to others before us, around us, and after us.

ON HOUSE / HOME

It is raining profusely outside. Inside, sheltered, your skin does not feel the wetness of the sky. To see the rain, you can look through the window at the drops pouring from the sky, focusing on their motion, bulbous shape, and intensity. Or, you can concentrate on the window pane, itself home to parasitic rain drops which try desperately not to slide down the pane to their deaths and which, in doing so, obscure the normal transparency of the glass. Although you are looking in a single direction, seemingly at the same point in space, and you are essentially observing the same phenomenon in both viewing cases, you can never see both at once. Your focus must flit back and forth between the two. This constant alteration of focus is similar to the way we approach the house/home dialectic. What is perhaps most interesting, is that without seeing the raindrops falling, it is impossible to empirically explain why the window is wet, and without seeing the wet window, one cannot not understand the viscosity of water, the friction produced by a seemingly smooth glass surface as compared to air.

PRINTS

There's something about seeing the hand-prints of others - of people you don't know but who have stood in this same space as you, and in some way share that space with you - which makes you feel more connected to the citizens of the world. It is a little like looking at the stars which men hundreds of years ago used to navigate their way through yet uncharted waters. While some might dislike these marks appearing built surfaces, for me the residue of the human-building relationship is quite charming.

When I stumbled across the photographs of the Beltgens Fashion Shop by Wiel Arets Architects, in Amsterdam, I couldn't help but be enamoured. Those fingers on corten. But even without the hand-prints overlaid the work is seductive in its simplicity. Wiel Arets continue to produce a range of exquisite work merging the old and new, the rough and fleshy.