CHARLOTTE PERRIAND

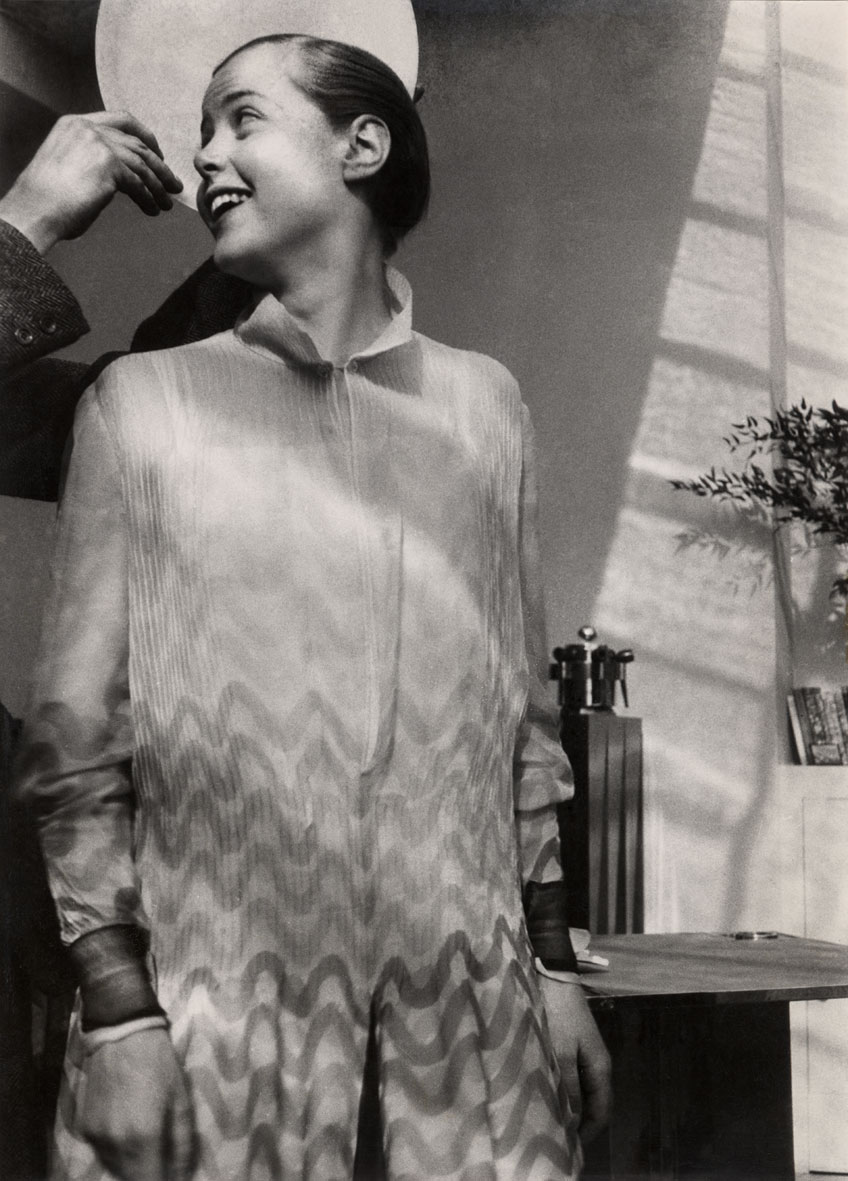

Charlotte Perriand in her studio in Montparnasse, ca. 1934.

Photo: Pierre Jeanneret, © 2010, ProLitteris, Zurich.

“The extension of the art of dwelling is the art of living.”

There aren't many people who seem better placed to discuss an art of living than Charlotte Perriand, whose life of 96 years had such breadth, impact and inspiration that it manages to continue to sing even now, 15 years after its end.

It is somewhat of a frustration, then, that not only her work, but her character are continually positioned alongside the demanding and prestigious Le Corbusier. For me, Charlotte is more than an adjacency to Corb, or a 'woman designer'. She is a muse: a strong mind with an immense sense of self, a body with which she engages in rich experiences of the world, a soul with an uninhibited capacity for creative production. Historian Mary McLeod takes up Perriand's case in her stellar essay Perriand: Reflections of feminism and modern architecture, published in the Harvard Design Magazine (2004), where she calls for histories of modern architecture, such as those that include Perriand, to look beyond reductive comparisons, and to seek to understand the richness and complexities of how gender is constructed and challenged through design practices.

Charlotte Perriand was woman of boundless design fluency, she was a master of translation, tirelessly working to transform her experiences of the world, through design, into visions of contemporary living. Architect, artist, traveler, designer, and urban planner, Perriand moved across scales, using her travel photography as a form of designerly-research, informing her projects. Her curiosity in the world around her seems to have been not only insatiable but also very precise: the cropping of her images revealing not only what she saw, but how she saw it.

Looking at Jeanneret's portrait of Perriand, above, I find myself looking with her, having first taken in her bare shoulders, the pearls, the way she has scooped her hair from her neck. Together we look beyond the flowers, beyond the deep reveals of the window, towards what in the blur we can only imagine is some kind of horizon. If there is an art of living it must start, I think, with an art of seeing, which, in turn, is linked with an almost unnerving intimacy to an art of being. I like to think that these are secrets that Charlotte knew too, and that they gave her a power to transcend the reductive assumptions of gender, and to quietly get on with what was important to her in making a life.

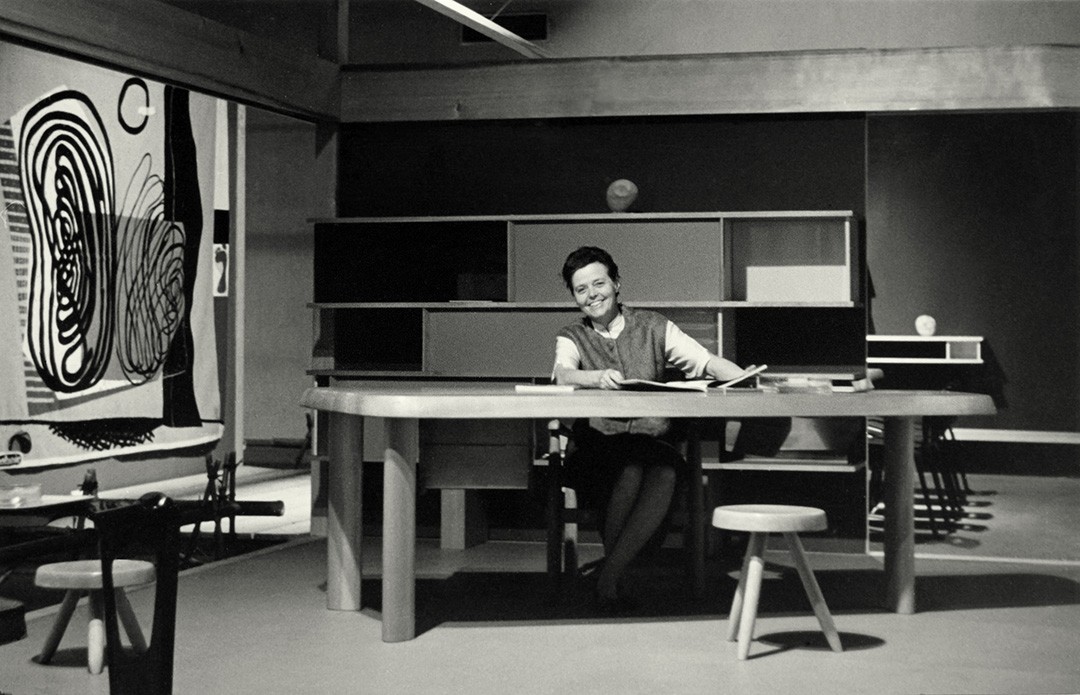

Perriand in her Studio